Discover more from The Freedom Analects

Sovereignism Part 7: Freedom Triumphs Over Fiat

A 12-part essay series exploring the disruption of the nation-state and the subsequent amplification of individual sovereignty during the Digital Age.

This series is loosely based on the 1997 masterwork: The Sovereign Individual.

“Exodus believes in empowering the individual to control their wealth and financial destiny and has provided financial support for the research and writing of this series. Exodus has no editorial control over the content of these writings.”

Mass-Psychosis

“It is not famine, not earthquakes, not microbes, not cancer, but man himself who is man’s greatest danger to man, for the simple reason that there is no adequate protection against psychic epidemics, which are infinitely more devastating than the worst of natural disasters.”—Carl Jung

A mass-psychosis is an epidemic of delusion. It occurs when a large portion of a society loses touch with reality and descends into madness. Like individual psychosis, a mass-psychosis manifests when agents of action lose touch with their respective arenas of action. Although the causes of mass-psychosis are multi-variate, I assert that money—a critical psychotechnological extension of the human mind and the highest form of private property—is an instrumental touchstone for an integrated relationship between individual agents and their respective socioeconomic arenas of action.

When money is centrally controlled, the pricing systems which coordinate human action are corrupted by bureaucratic whim: a noise which drowns out the signal of actual consumer wishes expressed through buying and selling. When pricing signals are corrupted by monopolization, it is increasingly difficult for market actors to assess the outcomes of their actions (profits and losses). Such mental confusion induces a retrogression in capital accumulation, and thus civilization. By introducing noise to this economic communications channel, entrepreneurial efforts are thrown into disarray, and deleterious sociocultural consequences ensue. Chief among these consequences of monetary manipulation is the phenomenon of mass-psychosis.

The Salem Witch Trials represent a small scale (yet well-known) historical example of a mass-psychosis. In the years 1692 and 1693 in what is now Danvers, Massachusetts, thousands of people, mostly women, were brutally murdered. Those murdered were not criminals, but rather the psychological scapegoats of a society under the spell of psychosis. After the frenzy finally burned itself out, there were scarcely any women left alive. Most people today know of this massacre. Less commonly known is that the decades leading up to the infamous climax of this mass-psychosis involved counterfeiting, capital controls, and statist struggles surrounding the “sovereign privilege” of currency issuance (aka the right to counterfeit currency).

In 1652, the Boston Mint was established in an attempt to prevent anyone (besides the mint) from counterfeiting currency. Strict “search and seizure” policies were enforced to prevent silver from flowing out of Massachusetts. However, these measures were of limited effect, and both counterfeiting and capital flight continued until the King of England issued an “Order of Council” against the essentially defunct Boston Mint in late 1686. Although written records are sparse after this, it appears that counterfeiting once again exploded in Salem in the run up to the climactic horrors of the Salem Witch Trials. By 1690, Boston took the bold step of becoming the first government in Western Civilization to issue fiat currency. By 1692, “witches” were being burned alive by a society under the spell of a mass-psychosis. Written records from the time detail some the counterfeiting activities leading up to this psychotic mass-slaughter:

“These Spanish dollars were crude ‘cobs’ struck out of a clump of silver, without even a standard shape. The Spanish minted cobs as quickly as possible, primarily as an easy way of inventorying and marking refined silver to be shipped to Spain where it would be melted down for various uses. The cobs had not been designed to be used as circulating currency. However, in the colonies these crude silver coins filled a serious economic void and were regularly used. Unfortunately, because of their irregular shape, many holders of these coins would clip a small piece of silver off the uneven edge of the coin to sell at a later date and then pass the coin off for its full value. As these coins circulated from one person to another they became lighter and lighter. The irregular shape not only encouraged clipping but it also made counterfeiting easier. Of course, counterfeiters would include as much alloy as possible so that the coin would contain less than the minimum required silver content (i.e. fineness).”

The history of money at this time was another example of Gresham’s Law playing out: incentives drove people to borrow and spend the soft money, and hoard the hard money. Other instances of counterfeiting leading to mass-psychosis include the bouts of 20th century totalitarianism, which will be discussed in the next installment of this essay series. As we will see, statism in its most extreme forms is effectively The Salem Witch Trials writ large, as both are made possible by the widespread counterfeiting of currency. The question becomes: how are the seemingly unrelated phenomenon of currency counterfeiting and mass-psychosis related? Again, the causes of mass-psychosis are multi-variate, but the contributing factor of currency counterfeiting (and property right violations more generally) is explicated by a branch of cognitive science called Material Engagement Theory.

The Blind Man’s Stick

“The mind does not inhabit the body, it is rather the body that inhabits the mind.”—Dr. Lambros Malafouris

An alternative to materialism, which regards meaning-making as a purely subjective mental process, Material Engagement Theory (MET) posits that meaning is an emergent property actors manifest through interaction with the material world. According to MET, “the mind” is not a strictly brain-bound entity, but is instead a complex of relational engagement incorporating brains, bodies, and things. Neither subjective nor objective, MET claims that meaning is a transjective phenomenon akin to Darwinian adaptation. For proponents of MET, “the world” is not a strictly segregated domain which humans survey with their senses to transmit information about to their internal processors. Cognition according to MET is instead a relational dynamic generated by an organism’s coupling to its environment, by means of appendage, tool, symbol, or—as we will show—money and property rights.

An important aspect to understand about life is the distinction between genotype and phenotype. Genotype is the digital information passed along about a life form, typically across generations. This typically includes the genetic material encoded in DNA, but can also include the cultural or institutional norms encoded through ritualized interactions with others. Phenotype is the physical manifestation of either of these genetically or culturally communicated instruction sets. Think of genotype as an algorithm of biological development (like the DNA of a tiger), and phenotype as the result of applying these instructions (the camouflaging stripes of the tiger). Genotype is information; phenotype is instantiation.

Often, biologists distinguish between standard and extended phenotypes. A ram’s horns, for instance, are a standard phenotype since they are produced as part of the animal’s biological development, whereas twigs used to build a bird’s nest are part of its extended phenotype, since the bird’s genetic code did not directly assemble its dwelling. Contributing significantly to their dominance of the world, humans are exceptionally adept at extending their phenotypes. Humans are “natural-born cyborgs” that specialize in designing, fabricating, and wielding ever-more sophisticated tools toward the satisfaction of their aims. Tools then, and engagement with material reality more generally, are extensions of the human mind. As renowned MET theorist Malafouris writes:

“If we accept that the mind evolves and exists in the relational domain as our most fundamental means of engaging with the world, then material culture is potentially coextensive and consubstantial with mind.”

Understanding the human proclivity for phenotypic extension is key to grasping (pun intended) the importance of MET. The example given by Malafouris to explain the relationship between cognition and the extended phenotype under MET is the Blind Man’s Stick (BMS) hypothesis. This theoretical exercise helps us to reconsider the traditional borders we mentally draw around brains, bodies, and things. Ask yourself: “where does the blind man’s self begin?” Does it begin at the edge of his skin, the middle of the stick, or perhaps the tip of the stick? To better understand MET, Malafouris suggests focusing on two key questions:

What does the stick do for the blind?

Does the biological boundary of the skin apply in the case of the blind?

To answer the first question, Malafouris argues that the stick enables the blind man to “see” by providing him a means of detecting the physical patterns relevant to the continual cognitive reorganization necessary for him to navigate his surroundings. In fact, much of the blind man’s cognitive processing of the haptic feedback provided from his “seeing stick” is processed in areas of the brain typically used for visual perception, but repurposed to assimilate tactile data inflows. For the second question, the “skin delineated” boundary is of little relevance, since the stick becomes incorporated into a complex perceptual process to such a degree that it effectively becomes “transparent”: the blind man does not see the stick in his mind’s eye, he sees through the stick.

Looking at the BMS in our mind’s eye, it is the tip of the stick’s contact with the material world which “discovers” the haptic feedback useful for a blind man to successfully navigate his surroundings. Without this tool, the blind man would become “a different animal entirely” as he would exhibit much lower fitness to his spatial environment (walking into walls, tripping over uneven terrain, etc.) In this way, the stick fundamentally improves the blind man’s competence as a conscious actor in the world; a change which is directly reflected in the cognitive changes afforded to him by a critical piece of his extended phenotype—the stick. The BMS, like all other tools, is just a mediating devices in an agent and arena relationship: a “material” pattern through which mind and matter interface.

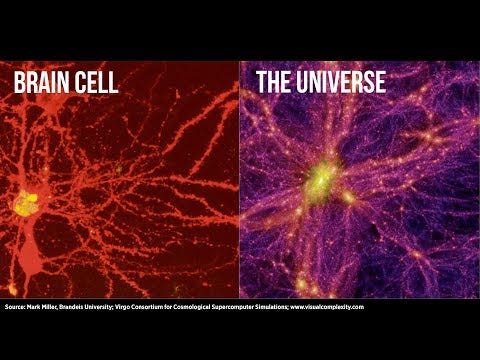

Differing from the substance-centric mental models widely held by materialists, MET conceptualizes the world as a kaleidoscopic complex of interpenetrating patterns. Many of these patterns are layered together, and are often self-similar, consistent with the fractal geometry of nature. Snowflakes, geological features, and organic structures all display fractal jaggedness and self-similarity across scales. Extended well beyond the physical boundaries of the skull, MET conceives of the human mind as an extensible pattern emulative of the environmental patterns within which it is immersed. In this way, patterns of mind (agents) and their environments (arenas) reciprocally interact, often mutualizing similar shapes and contours. In this view, mind and matter are prismatic mirroring patterns. Maybe this is why the advice from Jordan Peterson to “clean your room” is so effective for cleansing the mind!

MET explains why minds and markets—processes of distributed cognition denominated in money—are mutually reflective fractals. Money is the tool which scales the mind up into the market through exchange, and the market down into the mind through prices, with an ongoing reciprocity. Most simply, the free market is a matrix of minds interconnected through price signals. Seen this way, it is unsurprising that the conscious awareness associated with an individual mind is an error-correction mechanism similar to function fulfilled by free market dynamics. MET explains the interface mechanism of mind and matter, although it makes it difficult, if not impossible, to specifically delineate between the two. Taken to the spatial extreme, MET points to the observed similarities between the cellular architecture of the brain and the galactic superclusters of the deepest cosmos:

Mind, Matter, and Money

“Mind over matter. Money over all.”—Wayne Carter

According to MET, the brain is only a component of the mind. Human cognition, then, occurs not only within the brain about things, but also outside the brain and through things. Indeed, it is believed that the minds of pre-literate humans were engaged exclusively through things, with no need for mental representation whatsoever. Ancient man thought through action, with little reflection before or after. This may have inhibited his ability to plan, but it kept him “in close touch” with the present, which was useful for hunting and tracking. In light of this, the minds of our ancestors did not disappear with the deterioration of their brains, but rather are encoded in the intact archeological records that reflect their patterns of action. MET says that within the scope of human action and cognition, engaged matter is mind and mind is matter thus engaged. There is a reciprocity, or even a continuity, of influence between these traditionally segregated entities. As John Culkin succinctly describes this reflexivity of mind and matter:

“We become what we behold. We shape our tools and then our tools shape us.”

Or, as philosopher A. Illopoulos goes a step further to describe the apparent unity of mind and matter:

“Considering though that meaning is produced through habits, it would not be unreasonable to see matter as ‘nothing but mind that had such indurated habits as to cause it to act with a peculiarly high degree of mechanical regularity, or routine.”

For market actors, a significant interface between mind and matter is the money-expressed pricing system. Humans today think through money in many situations, like economic planning and negotiations. Money is one of the most important tools to human action: it is antecedent to psychotechologies that are as fundamental to thinking and acting as literacy and numeracy. In other words, we have been trading much longer than speaking or calculating. In fact, literacy and numeracy give us good examples of how deeply embedded psychotechnologies can become in the cognitive software suites of humans. Notice that we more often think through rather than about language, numbers, and money. For instance, today it is difficult to imagine structuring thoughts without words, because we virtually always think through words, to the point where word-denominated internal dialogue becomes invisible to the mind’s eye—just like the stick does for the blind man. The psychotechnological aspect of money is similar: we so often think through money, that most of us never stop to think about money. By way of analogy: money is the economic water in which all humans swim:

“There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says ‘Morning, boys. How’s the water?’ And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes ‘What the hell is water?’”

Money is where the human capacity semiotics meets human action. The ephemeral boundary between mind and matter is instantiated in the hybridity of money as a technology and psychotechnology. Technologically, money has historically required a physical incarnation to root it in the thermodynamic realities undergirding economics such as work, sacrifice, and scarcity. Psychotechnologically, humans across history have strived to maximally “informationalize” their implementations of money to optimize for its cognitive functions of calculating, negotiating, and reconciling exchange relationships. In terms of affordances, free market processes historically promulgated gold-backed currency as the ideal money: an informationalized monetary technology with a supply secured from debasement by the only thing no human can counterfeit—work.

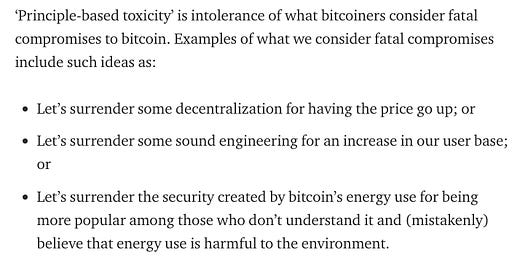

Affordances sought from money (divisibility, durability, recognizability, portability, and scarcity) explain both the selection of gold on the free market and its subsequent abstraction into currency. Gold is a monetary technology that exhibits scarcity reliably rooted in the thermodynamics of work. The application of currency “informationalized” gold in a way that let market actors treat it more like a psychotechnology and less like a (shiny, heavy, and cumbersome) physical monetary technology. As an aside: combining and building upon the economic properties of both gold and currency, Bitcoin virtually perfects money by being a purely informational tool that adapts to the work expended in its production process. A digital money that adapts to human action, Bitcoin is a “living money.” In this respect, and as I’ve argued before, Bitcoin may prove to be humanity’s most brilliant idea.

Circling back to the Blind Man’s Stick (BMS) hypothesis of MET, we can derive a useful analogy for understanding the impact of manipulating money on the human mind. First, it is important to understand that property rights function as the socioeconomic “grip” humans use to reshape the world according to their preferences. Starting from the axiom of individual self-ownership, property is the relationship between owners and assets, between socioeconomic agents and their arenas. When property rights are violated—as they are when currency supplies are arbitrarily inflated—feedback loops are disturbed, and market actors lose the ability to discern the specific consequences of their actions. Property rights subject to violation separate actors from the consequences of their actions, thus ameliorating their “skin in the game” and, eventually, contributing to civilizational collapse. Violations of property cause market actors to “lose their grip” on the world, creating an opportunity for statism to expand. In other words, the integrity of property rights is the means by which market actors “stay in touch” with reality. In this way, the inviolability of property is essential to mass-psychological health and stability.

“Hard money” is that with a supply that is hard to change, meaning that the property rights it enshrines are difficult to violate. “Soft money,” on the other hand, has a supply which is easier to change, meaning that the property rights which it emblematizes are easier to violate via inflation. Connecting money to the BMS analogy, hard money is like a rigid stick, whereas soft money is more like a limp noodle. Clearly, the haptic signals carried by an inflexible blind man’s stick—like the price signals carried by a money with an inflexible supply—are radically more salient, accurate, and useful than those propagated by the flaccid form of a soft stick or, its property right equivalent, soft money. Structural integrity of the stick is as important to the blind man’s navigational efforts as the integrity of the money supply is to effective entrepreneurship. As American Pragmatist John Dewey wrote about this “reflex arc” between agent and arena:

“The stimulus and response form specific phases of coordination, which helps to unify the disjointed parts given by the theory. The stimulus represents the conditions which have to be met in bringing about successful coordination, and the response gives the key to meeting these conditions; it serves as an instrument in affecting the successful coordination.”

Each human is a pattern of action stretched across spacetime. Wealth distributions strongly shape these action patterns of human beings, as most of the average individual’s life is spent working for money. For this reason, one’s net worth largely determines the thoughts and movements one makes daily. If you are a billionaire, the typical patterns of action you repeat are a far cry from those habituated by someone living paycheck to paycheck. And, as MET explicates, action largely determines how we shape the world around us, and thus how we shape our own minds. In this way, money—the ultimate socioeconomic implement of material engagement theory—deeply influences the imprinting of procedural knowledge into its users. Over time, individual self-reflection leads to this procedural knowledge becoming crystallized into semantic knowledge. Action is antecedent to speech and linguistic thought, which explains the ubiquity of spatial metaphor in human language. By perverting property rights, the accumulation of procedural knowledge is affected, thus creating distortions of mind and matter. In this way, inflation and all other violations of private property, at least partially, cause flare ups of mass-psychoses.

Money is foundational to human existence. It is the glue that holds together human action patterns, and it is the first weapon drawn in a fight. As Jeff Booth wrote on this familiar geopolitical progression: “Currency wars, then trade wars, then real wars.” As an accounting system for property rights, money is essential to the agent and arena relationship. Therefore, we can say that money is the prime mover of human action. It is the base layer protocol for mentally triangulating one’s position within socioeconomic hierarchies. This is why the counterfeiting of currency causes such adverse psychological reactions within populations. Seen this way, the horrors associated with The Salem Witch Trials can be more clearly understood. Given this fundamental connection of money and mind, it is not surprising that statists wield money to manipulate human action patterns and marginalize the mental fortitude of citizens whenever it suits their economic interests.

Remember: all human organizations are businesses, and all businesses are wealth acquisition strategies. Statism is a business strategy in which taxpayers are the crops standardized for harvest. Although statism remains the dominant mode of human organization today, it is often darkest before the dawn. Before diving into the darkness of statism in its most extreme form, let’s explore its ideological structuralism to show why it is doomed to fail. Despite the best efforts of authoritarians and politicians across history, there have been no sustainable implementations of statism precisely because the patterns engendered by freedom inexorably triumph over fiat.

“You can’t force someone to respect you, and respect is the ultimate currency.”

Sovereignism quite simply outcompetes statism for extremely pragmatic reasons. As the American Founding Fathers understood, freedom creates positive externalities, whereas fiat elicits negative externalities. Civilizations that embrace freedom become more prosperous than those which prioritize the forcefulness of fiat. Or, as Jordan Peterson says, echoing the findings of genetic epistemologist Jean Piaget: “equilibriated structures outcompete disequalibriated structures.” But what exactly does this mean, and what does it have to do with freedom vs. fiat? Let’s explore.

Freedom Triumphs Over Fiat

“The prosperity of government, like that of unions, was directly correlated to the leverage available for extortion. That leverage was much lower in the 19th century than in the 20th. In the 21st century, it will fall almost to the vanishing point.”—The Sovereign Individual

Human interaction within the scope of economics exhibits game dynamics. A game is any situation where there is competition over scarce resources: in the case of a board game, these resources are typically points or objectives; in the case of markets, these resources are productive factors (land, capital, and labor) and the purchasing power of money. Anytime there are potential winners and losers, a game is being played. A strategy is an approach to decision-making within the scope of gameplay. Strategies are based on the governing constants of the game: typically, these are the rules, but they can also be phenomenological factors such as gravity or thermodynamics. Actors formulate their strategies in anticipation of the actions of their competitors within the scope of these governing rules or factors.

In a game where the rules are not immutable, the super-dominant strategy is to gain control over the rule-making. In doing so, no matter what happens, the rule-setting player can always bend them to achieve victory. Said simply: to control the rules is to control the outcome of every game. Given the great power rule-making affords an actor, it is the most fiercely pursued strategy if it is an option. The problem, of course, is that no player wants to play a game where another player has arrogated themself the power to make (and continually remake, or even selectively break) the rules. Imagine you’re sitting down to play chess against an opponent who has the ability to change the maneuverability of his pieces every few turns—perhaps causing his pawns to leap long-distances across the board like a queen on one turn, or moving his rooks diagonally like bishops on another. Clearly, wielding such a tremendous power within the game of chess, the rule-making (or rule-breaking) player’s very existence would be extremely demoralizing to all of his opponents, as this asymmetric privilege would make the game of chess decisively unfair for all those he faced off against. In few words: ruler-makers always tend to go undefeated. This obvious principle is the true impetus of central banking:

“Permit me to issue and control the money of a nation, and I care not who makes its laws.”—Nathan Mayer Rothschild

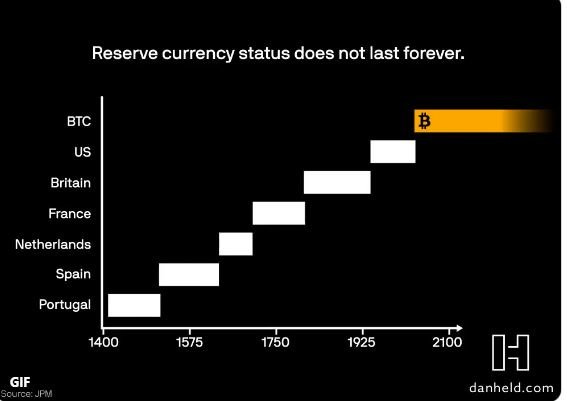

The problem with the power of rule-making is that there is nothing more contested in the sphere of gameplay. Rule-making is effectively the power to win in perpetuity, and what player in their right mind wouldn’t want that? However, rule-making is an expensive privilege to preserve. Because of the absolute power it imparts, players constantly fight to takeover the position of rule-maker when the rules are mutable. For this reason, rule-makers are forced to constantly expend great resources on defending their positions and enforcing their rules on players resistant to their power. This explains the periodic rise and fall of global reserve currencies historically:

A game with changeable rules is inherently unstable: it is a disequilibriated structure, meaning that the rule-makers inevitably incur the costs of turf protection and rule enforcement in their endless contentions to maintain control the game. Naturally, the question then becomes: how do these rule-makers pay for these costs of preserving their privilege? For rule-makers, the answer is straightforward: just twist the rules in a way that extracts resources from the other players, taking enough to cover protection and enforcement costs, leaving over some margin as profit. Of course, given the option of a less costly alternative, the players being taxed (I am using this term purposefully) in this way will defect from the disequilibriated game and choose to play another. Absent the threat of coercion or violence, this process causes actors to converge on the rulesets that are the most predictable, resistant to manipulation, and favorable to their self-interests. This is why the processes of pragmatic-truth-discovery on the free market converge on equilibriated structures: games in which no player incurs the protection or enforcement costs associated with a disequilibriated structure. When the rules are “discovered” in this way (see: substantively justifiable law) and voluntarily adopted by all, less expenditure for protection or enforcement is necessary. As a result, equilibriated structures naturally outcompete their disequilibriated counterparts. This unavoidable economic reality is why gold monetized on the free market, why internets supplanted intranets, and why Bitcoin is currently monetizing. In the long run, open, voluntary networks always outcompete closed, involuntary networks.

As you may have guessed, statism is disequilibriated, whereas sovereignism is an equilibriated structure. Nation-states expend tremendous resources standardizing, manipulating, and taxing their populations. These costs can only be paid when the cost-to-benefit ratio of coercion is sufficiently low. In other words, the profitability of statism is dependent on economic returns to violence that are higher than the attendant protection and enforcement costs. As market actors wake up to the undue taxation being inflicted upon them by central banks, they will take the rational course of action and sell their fiat currency positions for Bitcoin. This selling puts downward pressure on the potential inflation revenues of nation-states worldwide, as it accelerates the depreciation of fiat currency purchasing power. To retain at least some semblance of solvency, this will force the hands of nation-states who will have no choice other than to compensate for inflation revenue shortfalls with increases in direct taxation. Expect to see increasingly exotic enforcement actions like taxing unrealized capital gains, eminent domain, bail-ins, and the raiding of safety deposit boxes as the financial desperation of nation-states escalates. The end game of all this? All self-interested market actors (ie. all market actors) holding the only money in human history with a 0% terminal inflation rate, and a high resistance to all other tax schemes thanks to its digital, hyper-portable nature. In this way, Bitcoin-enabled sovereignism is the death bell of statism, and the birth of unparalleled prosperity.

“Whenever circumstances allow people to reduce protection costs and minimize tribute paid to those who control organized violence, the economy usually grows dramatically.”—The Sovereign Individual

The only effective survival strategy for nation-states is to buy Bitcoin. As a result, states will inevitably be forced to shrink, increase operational efficiency, and strive to satisfy citizen demands. As the competition to attract sovereignists for residency heats up, nations will be forced to offer better services at more affordable prices, delivered in more innovative ways. The end result will be nothing like the nation-states we know today. “Networked states” (like those envisaged by Balajis) are one possible outcome. People will simply go where they are treated best, and will not be tethered to any single geography. In short: hyper-portable capital empowers location-agnostic capitols. Statism is destined to dissolve in the “digital acid” of limitless free exchange and plunder-proof property. Sovereignism wins by virtue of being a coercion-free meritocracy.

MET teaches us of the concordance among creators and their creations. When intervention by fiat is imposed, the discovery processes necessary for healthy cognition are disturbed, thus contributing to mass-psychosis. Relevance realization can only be established between agents and arenas through a consensus of voluntary actions. When property rights are violated through inflation or other means, market actors “lose sight” of reality and become mentally marginalized.

Money softening in the hands of market actors is equivalent to the structural disintegration of the blind man’s stick, which obscures agent and arena interrelations, causing human action to fall into destructive patterns of disharmony. Integrity of perceptual tools—like the rigidity of the blind man’s stick or the inflexibility of the money supply—are indispensable to the successful navigation of socioeconomic arenas by agents. Structural disintegration of these tools is a cause of psychosis and decivilization.

Fortunately, the absolute integrity of 21M Bitcoin offers great hope for a world suffering under the spell of state-induced psychosis. In Part 8, we will step into the darkness of statism taken to its most extreme form: totalitarianism. Fortunately, sovereignists have physics, economics, and game theory on their side. However, the road out of statism will likely be a bit treacherous. But in the end, it will be worth it.

“Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered, yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”—Thomas Paine

Thank you for reading Sovereignism Part 7: Freedom Triumphs Over Fiat.

PODCAST

SOCIAL

SUPPORT

Send Bitcoin to my PayNymID: +tightking693

RECOMMENDED BUSINESSES

Subscribe to The Freedom Analects

Written works exploring truth, power, freedom, money, economics, virtue, sovereignty, philosophy, and other enigmas of existence.